The Role of Emotional Solvency in Police Performance: Addressing the Failure to Engage

Society rightly expects highly capable police officers that are able to manage interpersonal conflict across a wide spectrum, from an emotionally charged conversation to the tense uncertainty of combat. Police behavior not in alignment with community expectations culminates in unnecessary conflict, community disillusion, and public distrust. These challenges that occur in the human-to-human exchange are at the point I identify as the police-to-citizen intersect.

Police Officers are Human

Our greatest fears and disappointments are realized when officer behavior does not appear to align with our department’s organizational philosophy and our community values. The core of controversy occurs when a representative of our government—in this case, a police officer—commits violence upon the constitutionally protected. This is never palatable. For the uninitiated or inexperienced, it can be shocking and unpleasant to see. Even though the Supreme Court does not require minimal force, community outrage can erupt when an officer exercises discretion to use a level of force that is not the least intrusive option available. Internationally recognized police trainer, Steve Ijames eloquently calls these situations, “Lawful but awful.â€

There are a number of causes that contribute to police behavior that misses the mark. The primary reason falls under the category called human performance factors. Police humanity is not an excuse for errant behavior but it does lend insight. The primary human performance factor is quite simply because, police officers are human, and as humans, sub-optimal performance is to be anticipated.

Emotional Solvency is the Foundation

As a leader, supervisor, and as a trainer, my favorite benchmark terms are; deliberate, and purposeful. To that end, the goal of police training is to provide a measured and disciplined response to our communities. There is a gap between input and output, between training environment and real-world performance and it torments us all. It is easily observable in force incidents, officer-involved shootings, and even during criminal interrogations.

Emotional solvency is the foundation for human performance. It is what undergirds the desirable behavior pattern that we see in high-performing officers. Solvency is the possession of assets in excess of liabilities: the ability to pay one’s debts. In the years I have spent creating warrior-protectors, emotional solvency is the currency that distinguishes between those that can and that cannot, the willing and the hesitant, the ‘I am’ and the ‘I-wish-I-were’.

The idea of emotional solvency arose out of a conversation with my friend Stewart Rouse. I had been presented with a video of an officer who was screaming, yelling and pointing his firearm at a group of people and within the context of the video there did not seem to be any reason or behaviors that explained or justified the officer’s behavior. I did not observe a stimulus that merited the officer’s actions. Stewart agreed that the officer did seem to have a $50 problem, meaning a low-threat environment, but the officer did not have the fifty bucks to solve the issue. So while the threat level was minimal, the officer did not have the solvency to address the matter. Because he was grossly underfunded for the task at hand he was insolvent or he lacked the solvency to withstand the emotional rigors of the situation though they were certainly not extreme circumstances.

When you observe an officer exhibiting behavior that is seemingly excessive for the stimulus presented, such as too much fear or terror, you are observing an officer that has found the self to be insufficient for the task at hand. Quite simply, the officer has written a check that they do not have the emotional assets to cover. In a moment of truth, they have found themselves lacking. This is not a moral judgment or condemnation. It is however, a conviction.

The Humanity of the Warrior is Integral to Performance

I am thankful for those before me:Kenneth Murray who gave us Training at the Speed of Life; Brian Willis, thought leader and author of W.I.N. and W.I.N. 2: Insights Into Training and Leading Warriors, Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, coauthor of Warrior Mindset: Mental Toughness Skills for our Nation’s Peacekeepers and many others. Together these authors recognize and speak to the humanity of the warrior as being integral to performance. However, collectively, most literature regarding police performance points to physiological arousal—such as an increase in heart rate and breathing rate—as the primary contributor to poor performance. This is a narrow approach that I call the classical perspective. The classical perspective offers little insight into the actual root cause of failure during police-to-citizen interactions. Also, from this perspective, the self-management tools typically offered are limited to such tactics as; reassess and reframe officer perspective, tactical breathing strategies, and positive self-talk. Though valuable, these interventions are typically used either post-event and in preparation for more future encounters, or they are implemented after the physiological arousal has already begun to diminish the officer’s capability. These efforts are a clear example of too little too late.

Perception, Cognition and Decision Training

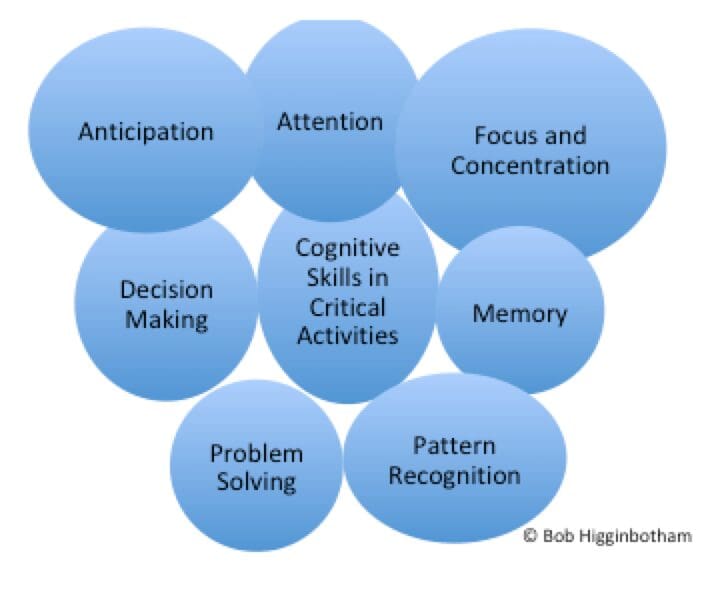

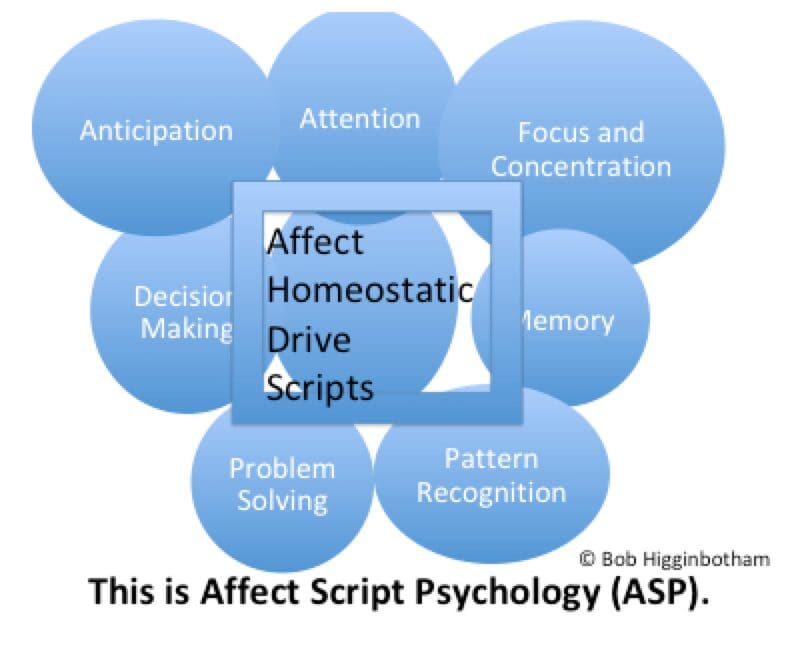

Joan Vickers, in Perception, Cognition and Decision Training, defines cognitive skills as; focus and concentration, anticipation, attention, decision-making, memory, problem solving, and pattern recognition. For years, I misattributed cognitive skills as the reason for the human performance failures we are seeing.

As trainers, we are experts in recognizing and teaching the cognitive skills. But, we need to understand how emotions contribute to less-than-optimal-performance in all high-stakes environments: on the street, down the back-alley and in the interview room.

All Force Decisions are Value-Laden Decisions

In order to comprehend the emotional magnitude of force decisions we must know and understand that all force decisions are value-laden decisions. That is, the decision to use force is a uniquely individual decision that cannot be separated from what the officer, at his or her core holds most dearly—the relative value of one’s own life when weighed against another being.

The single point of failure—of these value-laden decisions we so highly prize—occurs at an intersection where emotions are derived. This intersection is biological, psychological and social. (Biopsychosocial)

You will recall that most police training relies on cognitive skills, as in shoot/no-shoot decision training. A missing component from our training is the management of emotions. Most trainers will rely on inducing stress through time compression and the application of external variables such as the threat of pain with impact munitions.

This training protocol is insufficient because it does not address the very essence of the human being.

Adaptive Hesitation

Any seasoned trainer will be able to tell you that they have many times, during training exercises and on the street, observed police recruits fail to engage a hostile subject. Sometimes hesitation is just a lack of stimulus adaptation: you experience stimulus adaptation when you put your shirt on in the morning. At first, you feel and you are aware of your shirt. Shortly you don’t even know it is there. The recruit has not experienced the volatility of human conflict such as in a large-scale disturbance, a domestic violence call or a street brawl. We accomplish stimulus adaptation by introducing the trainee to loud yelling and screaming, loud music, etc. during training. This type of hesitation is adaptive hesitation and it is not contributing significantly to the overall problem of officer performance. Time and experience alleviates this type of hesitation.

Avoidance/Withdrawal

Hesitation that manifests itself during moments when personal safety is in question is the activation of a defensive behavior known as avoidance or withdrawal. Risk management is a proactive decision making process that guides behavior and acknowledges the responsibility to do something. Avoidance and withdrawal is to shrink back from the threat and diffuse personal responsibility. Avoidance/withdrawal looks very different and it has a very different quality than adaptive hesitation. Experienced trainers can spot the difference between adaptive hesitation and avoidance/withdrawal. However, they may not know why it occurs or know how to resolve the issue. In police culture, the usual response is to place the trainee in an as many hot or volatile situations as possible with the hopes that the recruit will somehow mysteriously develop the ability to navigate in the toxic environment of human conflict or they will self-identify and resign or they will wash out of the training program. This solution leaves a lot to chance. Police attrition/retention issues further exacerbate this problem because Command Staff may be willing to overlook or even circumvent their own training program, keeping employees that cannot be safely deployed to protect innocent and vulnerable people.

The Source of Human Emotion

Our conversation has arrived at the biopsychosocial intersection that I earlier called the source of human emotion. It is here that we can learn to understand how and why things go wrong between the citizens and their police. Three parts make up the intersection—affect, cognition and script—which I will explain.

Affect

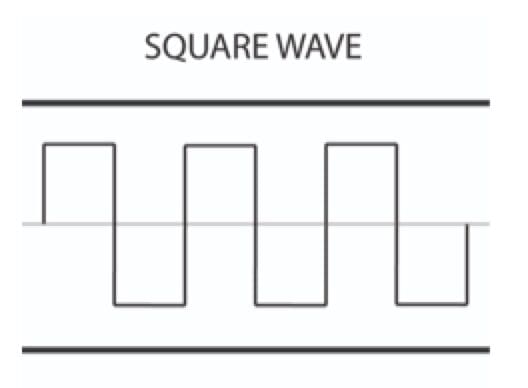

Affect is our internal representation of the external stimulation we are receiving. Our bodies magnificently and quite literally recreate our external world in the form of neural density. A gunshot is an easy example. A gunshot occurs very rapidly and almost simultaneously disappears. It could be described as a square wave and it looks like the figure below.

If the gunshot is unexpected it looks and feels just like the picture—a rapid onset, a very short duration, and an equally rapid offset. This is what we call a startle response. When something startles us, we experience and feel a density of neural firing that equates to the square wave you see in the diagram. All affect is just this, a correlate or duplicate of what we are experiencing. By the way, we do not only experience affect from external stimuli. We can generate our own affective responses any number of ways including remembering a prior event, watching a movie, or even watching another emotionally charged person. The purpose of affect is to let you become aware that something is important.

Cognition: Prior to Your Awareness, the Impulse to Act Exists

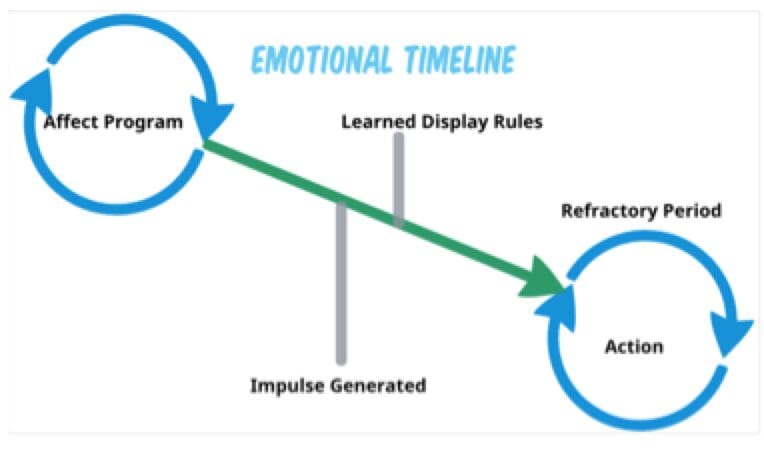

For purposes of our conversation, cognition is to know. It is when you are aware that you are reacting physiologically to something in your environment. The first moments of cognition, or awareness that you are undergoing physiological change, is a feeling state. It is now that you will begin to construct how or whether you will respond to what your feeling state. On a

timeline it looks like the picture to the right.

The affect program will generate an impulse to act in around three hundred-fifty to five hundred milliseconds. Your feeling state, awareness or cognition will begin around five hundred milliseconds. That is important! Look closely as I just told you that emotion is first and always physiological in the form of affect. And, the affect program provides an impulse to do something, prior to your own awareness that the impulse to act even exists. Your body is telling you to do something but you aren’t even consciously aware of the impulse yet.

An Affective Response

This means that when too much is happening too fast, the human being—including a police officer—exhibits an orchestrated set of responses; facial muscles, intestinal system, respiratory system, skeleton, autonomic blood flow changes and vocalizations, all occur without prior to any cognitive interpretation or even awareness. Does this sound familiar? So how do we restore order to this orchestrated chaos?

Scripts are Rules for Behavior

The question we have asked ourselves is what can we do to understand how police officers make decisions in highly charged emotional contexts. The answer is that we must recognize how our scripts influence our behavior. A script is an ordering rule or an, ‘if this then that-rule’ that we use to guide our behavior so we don’t have to decide what to do each time a similar situation is presented us.

The ordering rules are guidelines to help us maximize the positive we want to experience and to minimize the negative that we don’t want to experience. Think about eating something that makes you feel sick. The mere odor of that food will evoke memories of your distasteful experience and you do not have to decide once again whether to eat it or not. The decision is a foregone conclusion in the form of an ordering rule that we no longer eat that item or anything that even closely resembles it in appearance or odor. That is a script.

Some scripts we bring with us as individuals, we got them from our families. Some scripts are indoctrinated into us through the police training mechanism and police culture. We are continually overwriting, rewriting or reaffirming our scripts as we go about our daily lives. The most important scripts are our ideological scripts. It is these scripts that define what is important to us and moreover, why it is important. What I have just described to you, affect, cognition and scripts, is derived from a body of work created by Silvan Tomkins. It is known as Affect Script Psychology. (ASP)

The Single Point of Failure

Recall that I said all force decisions are value-based decisions that come with an emotional magnitude, wherein we identify the relative value of our own life versus that life of another.

I again assert that this biopsychosocial intersection where emotions are derived is the single point of failure. It has been far too long ignored. The role of emotional solvency in police performance requires we integrate ASP into police training. Below you will see that Affect Script Psychology is the overlay for the cognitive skills. This is also called the Human Being Theory and it is the glue that holds our training together.

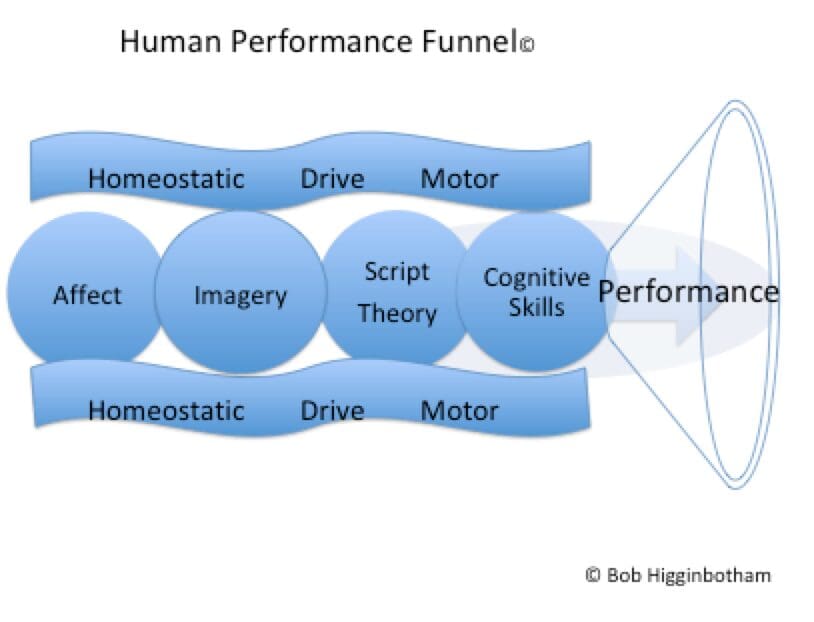

Human Performance Funnel

I have found myself a more effective trainer using what I describe as a human performance funnel. The training funnel combines ASP and recognizes the human being as a system. We can no longer separate the cognitive skills that we so long have chased without placing those skills into the whole framework that comprises the human being and recognizes the

humanity of the officer.

No one wants to slow down an officer’s reaction to a deadly threat. To insert thinking and feeling into the emotional timeline during extreme time compression such as a gunfight would be ill advised and would likely have unintended deadly consequences.

With the proper training paradigm, which includes a full understanding and application of the human being theory, as a system, we can enable police officers to protect the sanctity of the constitution, align with our organizational philosophy and our community values during highly charged human-to-human interactions, without the loss to their critical performance capabilities.

Bob Higginbotham – Board Member of the Tomkins Institute, Director of Blue Line Science Group, Director of EIAUSA, a veteran police officer, Detective Sergeant, Cyber-Crimes Task Force Supervisor and Retired Police Captain.